Mastering PID Control: The Hidden Engine Behind Robotic Joint Precision

Behind a robot’s ability to execute precise actions such as grasping, assembly, and collaboration lies the decisive role of stable control within its joint modules. The core technology that enables these modules to achieve “stable, accurate, and fast” control is the PID control algorithm. Mastering PID parameter tuning is like equipping the joint module with a “smart brain,” allowing a deep understanding of the PID control logic and tuning methods used in robotic joints.

The PID control algorithm—short for Proportional-Integral-Derivative control—is one of the most widely used closed-loop control algorithms in industrial automation. By comparing the actual operating state of a joint module (such as position, speed, or current) with the target state, it calculates the error and uses the coordinated action of the P, I, and D components to output a control signal that adjusts the motor. This drives the joint to accurately converge toward the target state. These three parameters function like a three-legged support, jointly sustaining the module’s control precision.

The proportional gain (P) provides the “basic driving force” of PID control, responding directly to the control error. When the actual position of the joint deviates from the target position, the P term outputs a control amount proportional to the magnitude of the error: the larger the error, the stronger the control action. In joint module applications, P directly affects response speed: too small, and the joint moves sluggishly and reacts slowly to sudden command changes; properly tuned, it enables rapid response and quick error reduction. But bigger is not always better—an excessively large P gain causes “overreaction,” leading to repeated overshoot and oscillation. For example, when commanded to move to 90°, the actual position may swing between 85° and 95°, unable to stabilize.

The integral gain (I) is key to eliminating steady-state error. In high-precision scenarios, even with a well-tuned P term, a joint may still settle with a slight offset—such as stabilizing at 89.9° instead of the 90° target. This static error can significantly impact operational accuracy. The I term accumulates the error over time and continuously outputs corrective control to gradually eliminate the offset. Proper I tuning can also improve response speed, but too much integral action accumulates too quickly, causing excessive control output and violent oscillations that undermine system stability.

The derivative gain (D) acts as a “stabilizer,” mainly suppressing overshoot and oscillation. When a joint rapidly moves in response to a command, it tends to “overshoot,” such as moving past 90° to 92° before coming back, which prolongs settling time. The D term predicts the trend of error change and outputs a reverse control force early to counteract the inertia-induced overshoot. However, D must be tuned with caution: too small, and it cannot effectively reduce overshoot; too large, and it amplifies sensor noise, causing irregular jitter or even disrupting the control loop.

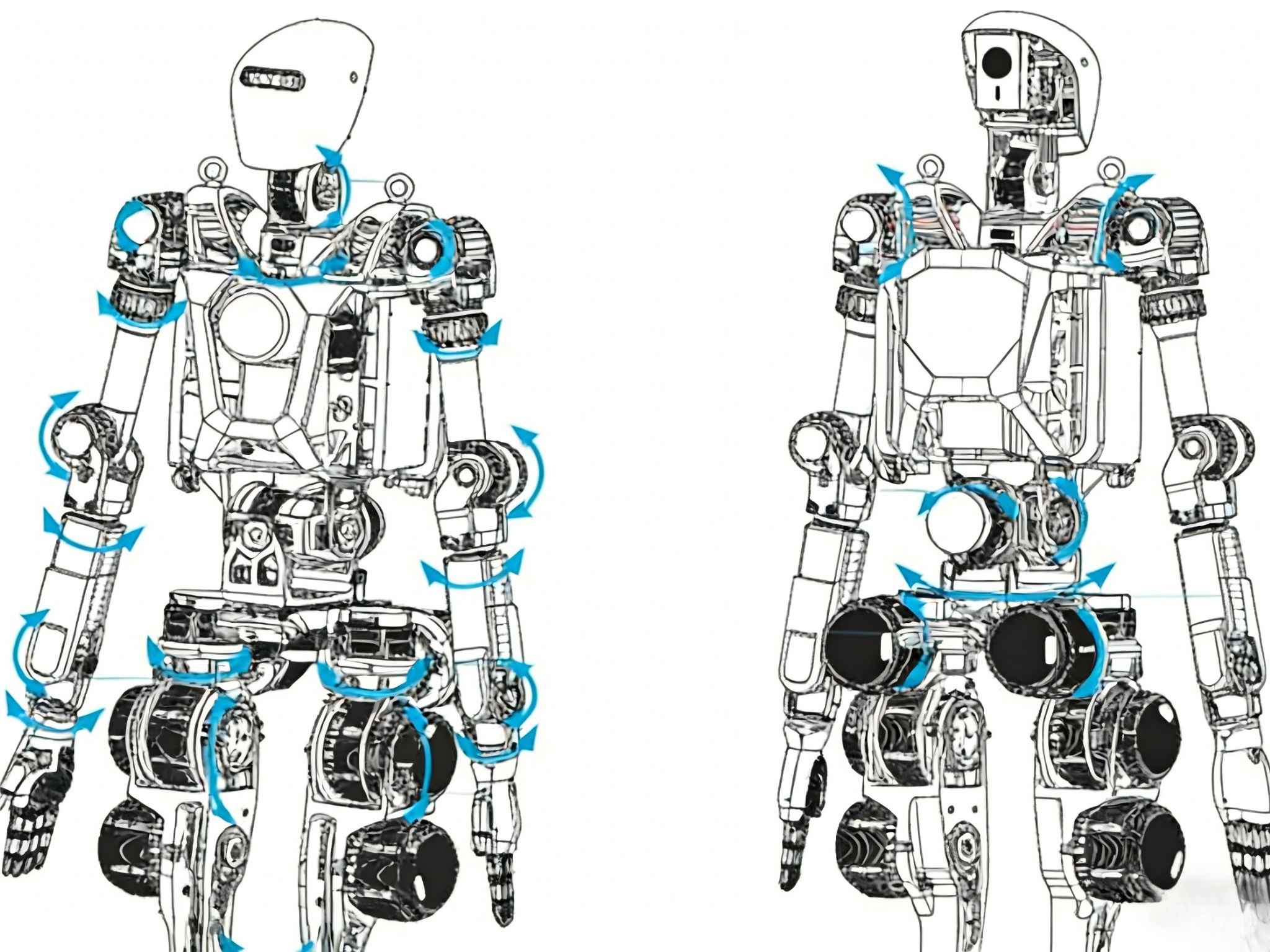

Joint modules typically adopt a “three-loop nested” PID structure: from inside to outside—current loop, speed loop, and position loop. Tuning must follow the principle “inner loops first, outer loops later.” The current loop directly controls motor current, determining output torque and serving as the most fundamental control layer. The speed loop builds on the current loop to adjust rotational speed, and the position loop—being the outermost layer—generates speed commands based on position targets. The stability of outer loops relies on the inner loops; skipping the current loop and tuning only the position loop will destabilize the system, causing severe oscillations or loss of response.

The key indicators for evaluating PID tuning include steady-state error, dynamic tracking error, and overshoot. Steady-state error reflects post-settling accuracy, dynamic tracking error reflects accuracy during motion, and overshoot relates to system stability. Ideally, high-quality PID tuning achieves “zero steady-state error, precise dynamic tracking, and minimal or no overshoot,” enabling the joint module to respond quickly while maintaining stability and precision.

PID tuning has no universal formula; it must be optimized according to each joint module’s load characteristics and application context. But by mastering the core logic—“P adjusts responsiveness, I eliminates steady-state error, and D stabilizes the system”—and following the principle “tune inner loops before outer loops,” then iterating through real-world testing, one can optimize joint module performance and provide a solid control foundation for precise robotic operations.

Read More

Learn more about the story of HONPINE and industry trends related to precision transmission.

Double Click

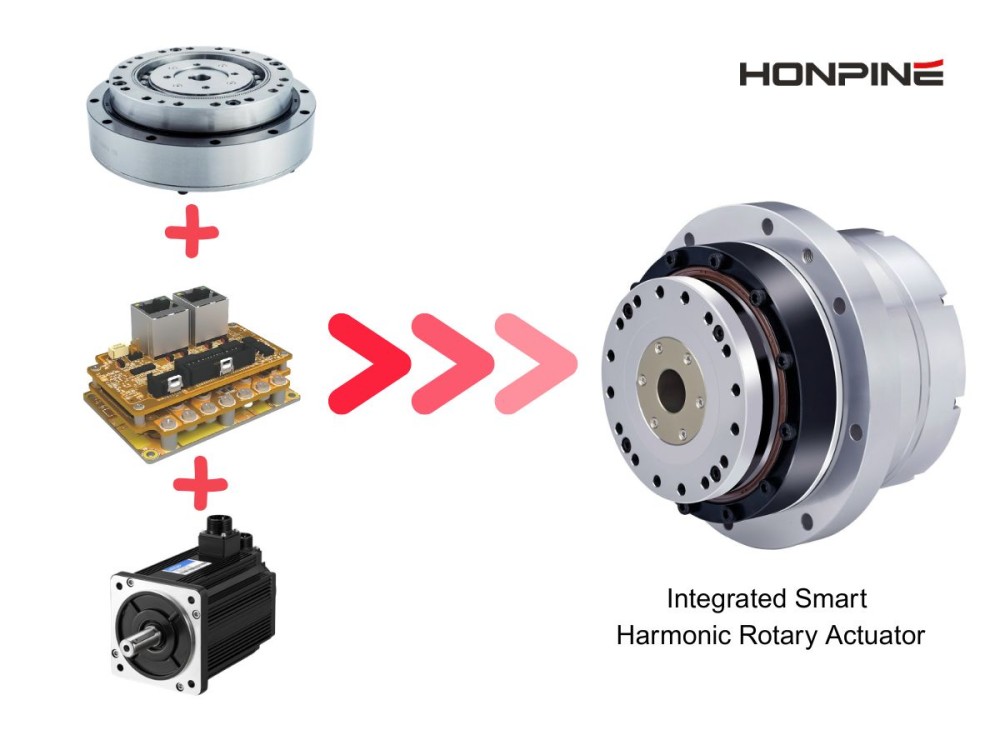

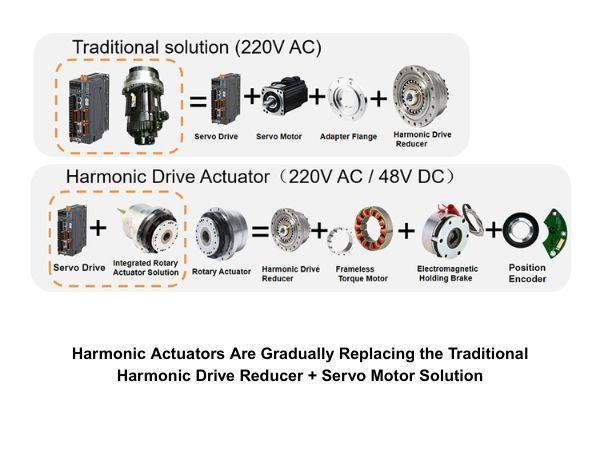

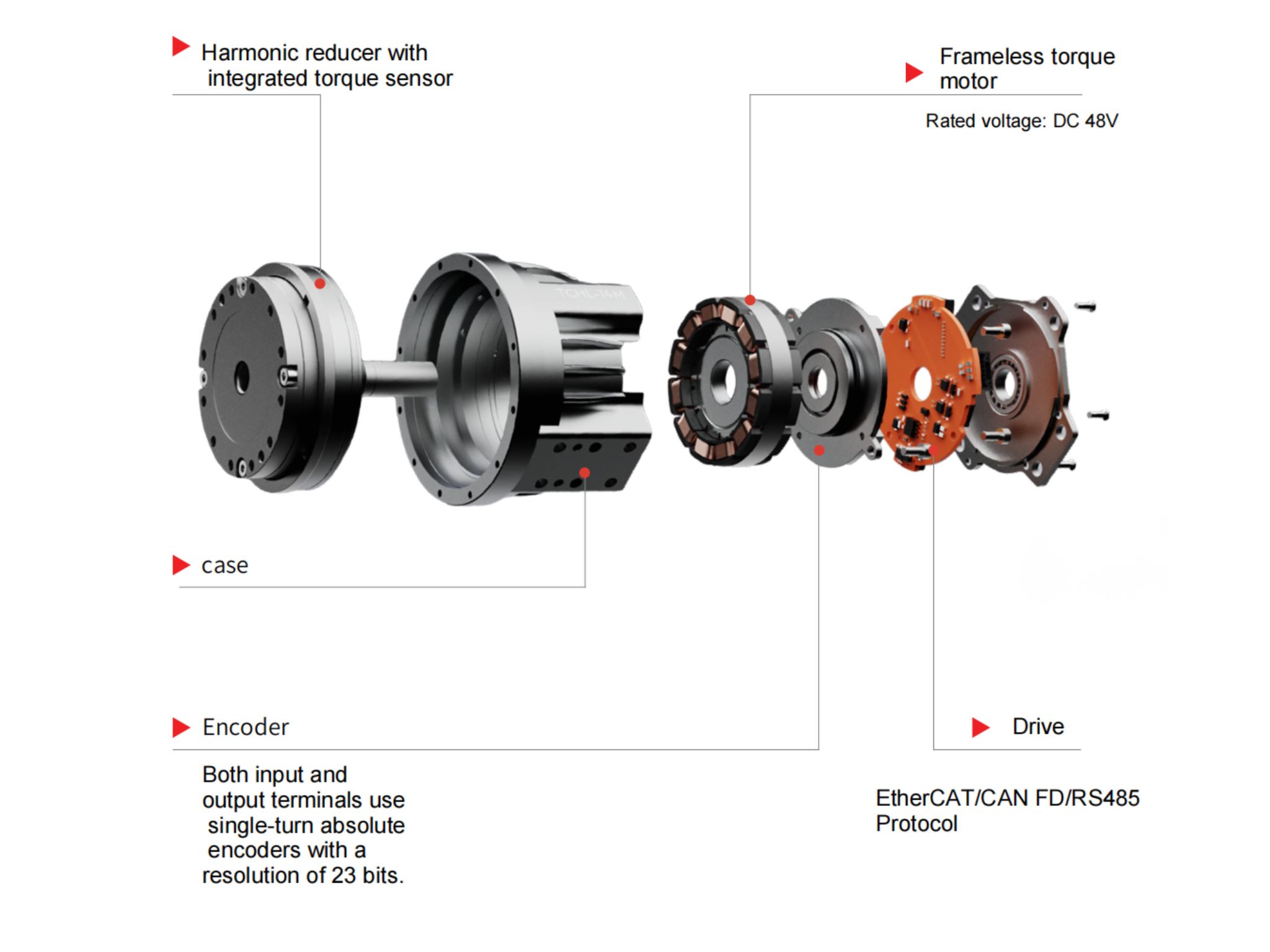

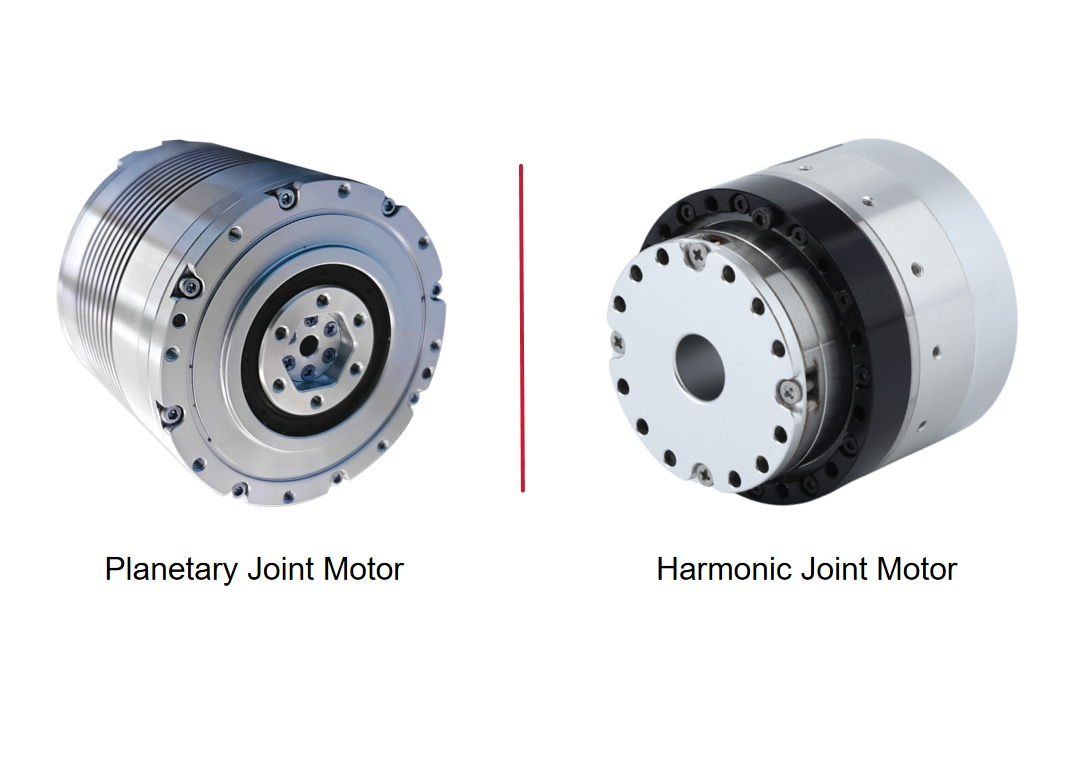

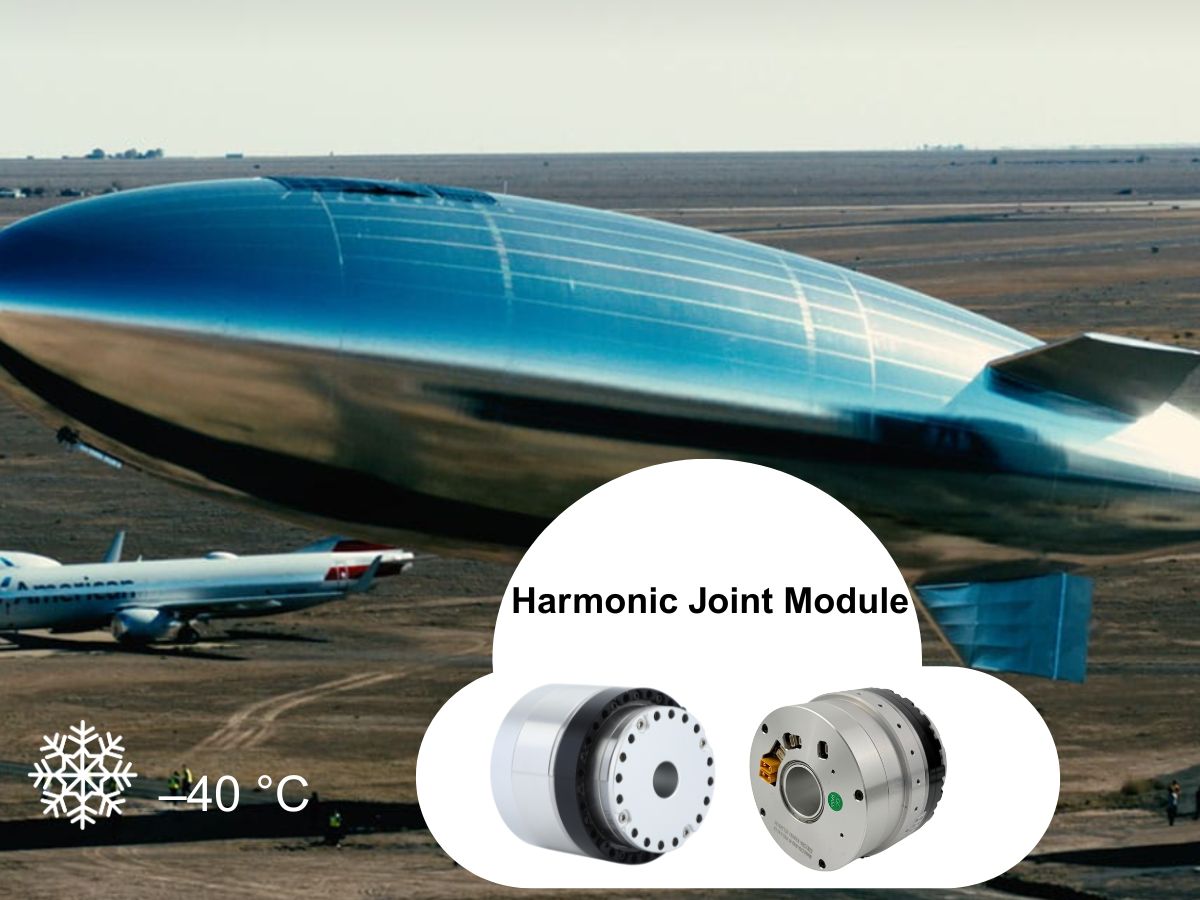

We provide harmonic drive reducer,planetary reducer,robot joint motor,robot rotary actuators,RV gear reducer,robot end effector,dexterous robot hand