How Joint Motors Are Redefining the Future of Robotic Arms?

The rise of embodied intelligence is pushing the design of robotic arms toward an entirely new paradigm. No longer are they merely tools for executing preprogrammed trajectories; instead, they are becoming extensions of an intelligent agent’s “proprioceptive body” in the physical world—capable of active exploration, dexterous manipulation, and safe interaction. This fundamental shift in objectives places unprecedentedly stringent demands on the underlying hardware architecture, control logic, and software ecosystem of robotic arms. So what kind of joint motors will future robotic arms need to use?

Operating Principles of Robotic Arms and Motors

In terms of working principles, robotic arms rely on the coordinated operation of motors, drivers, and high-precision sensors. Motors act as the power source, providing the driving force for motion. Drivers are responsible for precisely regulating the motor’s speed and torque to ensure that the arm’s movements achieve the desired accuracy. Sensors continuously monitor information such as joint position and applied force; once a deviation is detected, feedback is rapidly sent to the control system so that adjustments can be made.

For example, when a robotic arm needs to grasp a fragile object, sensors detect the applied force and immediately relay this information to the control system, allowing the arm to apply force gently and avoid damaging the object.

Core Factors in Selecting Robotic Arm Joint Motors

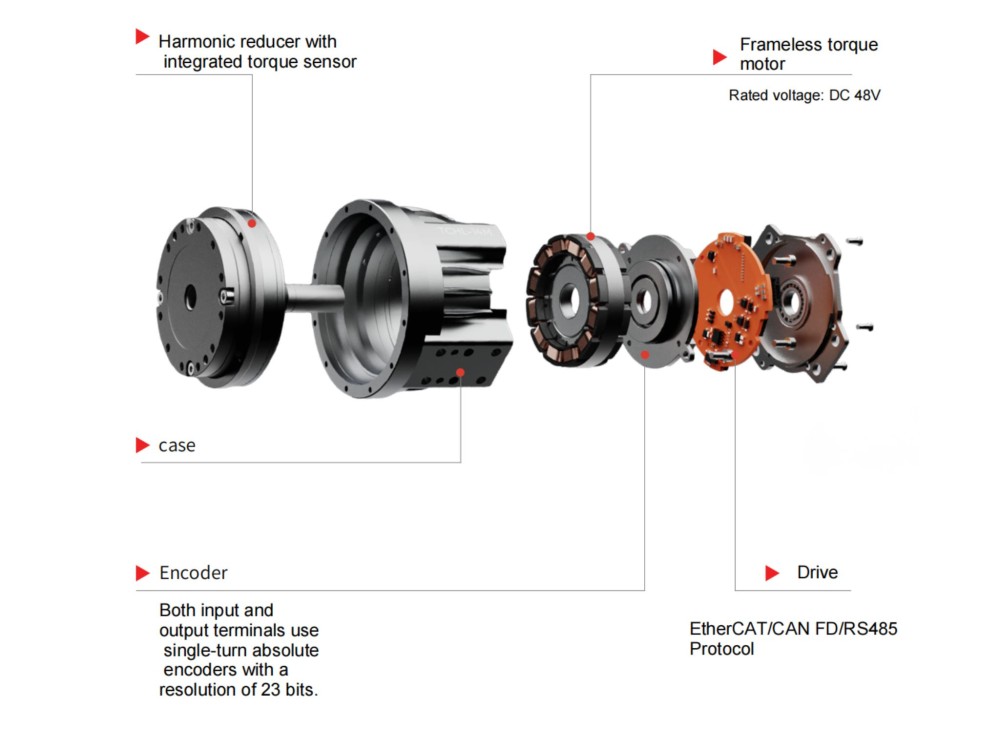

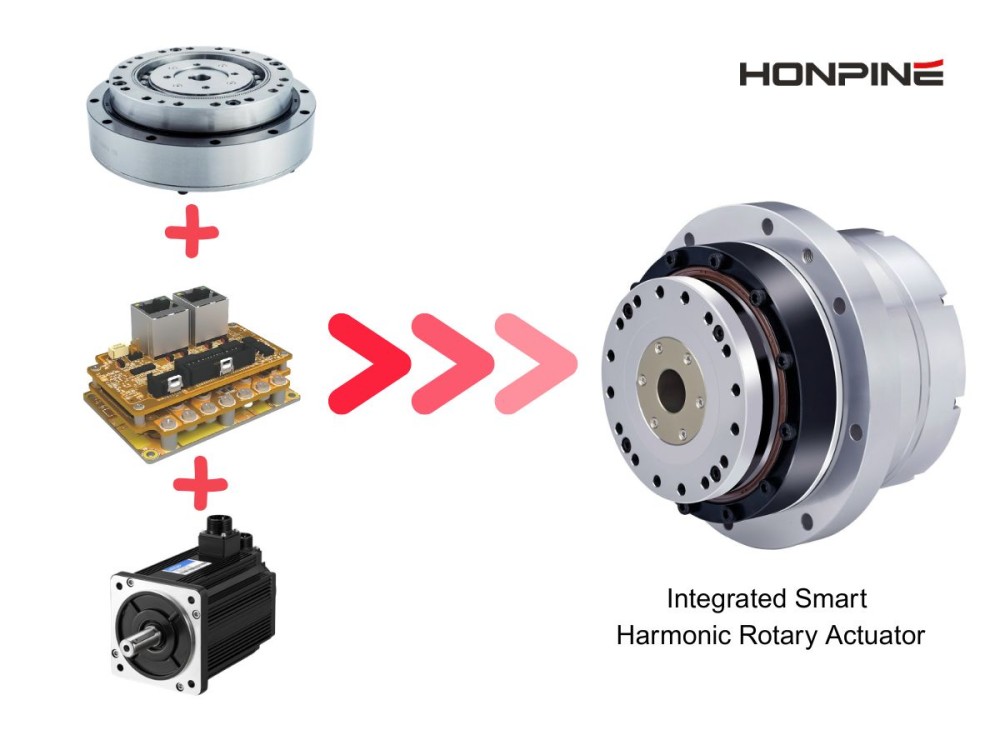

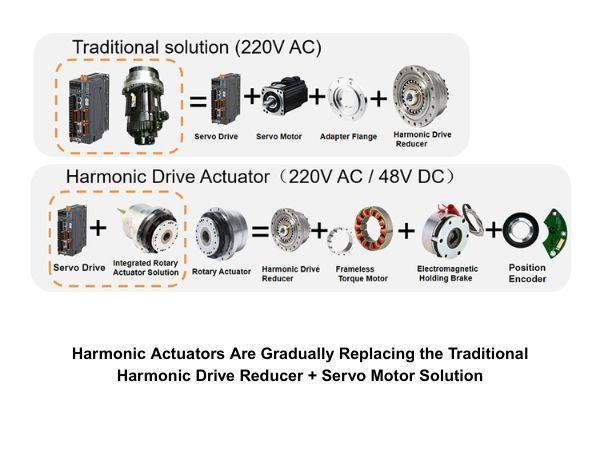

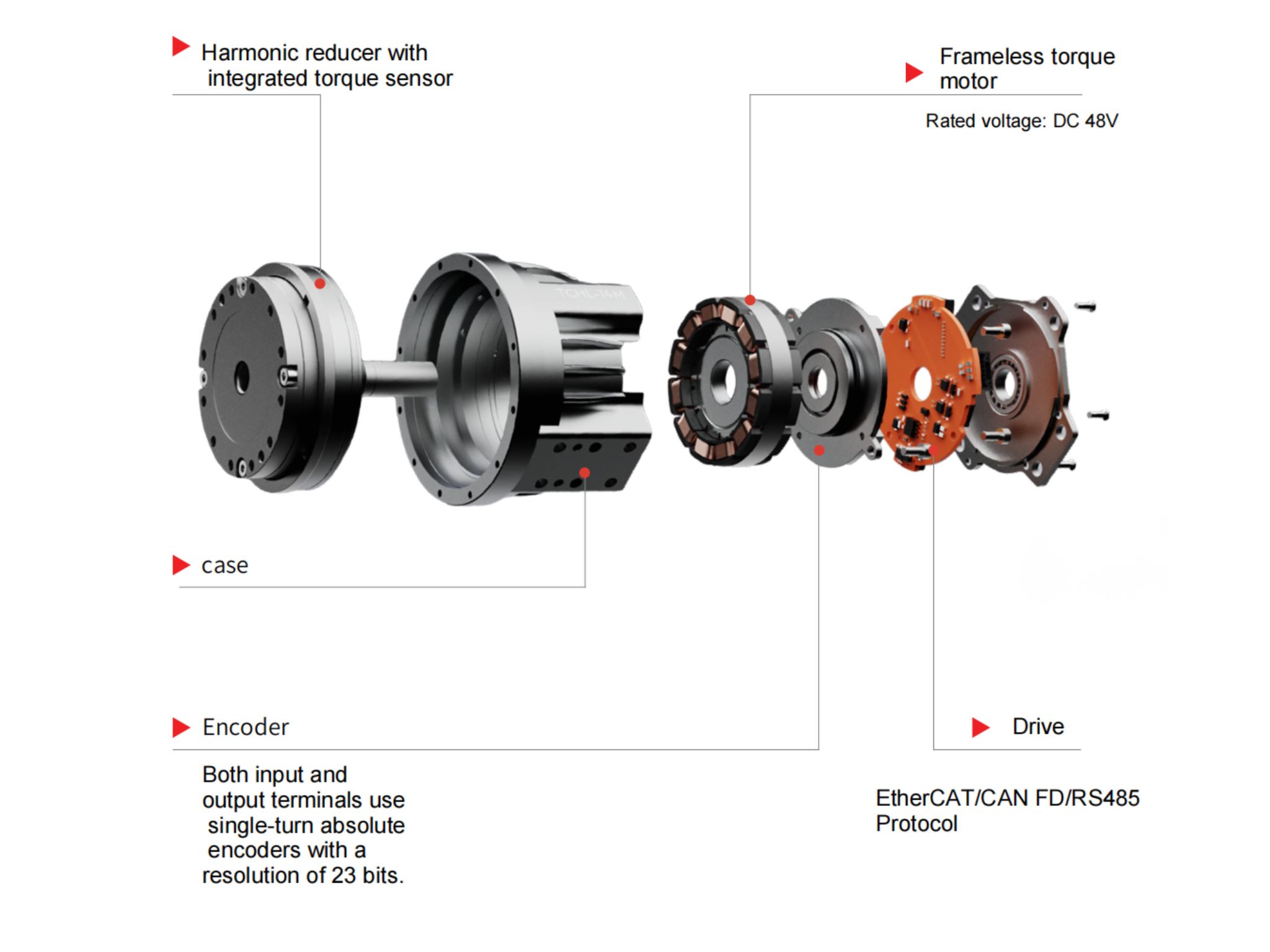

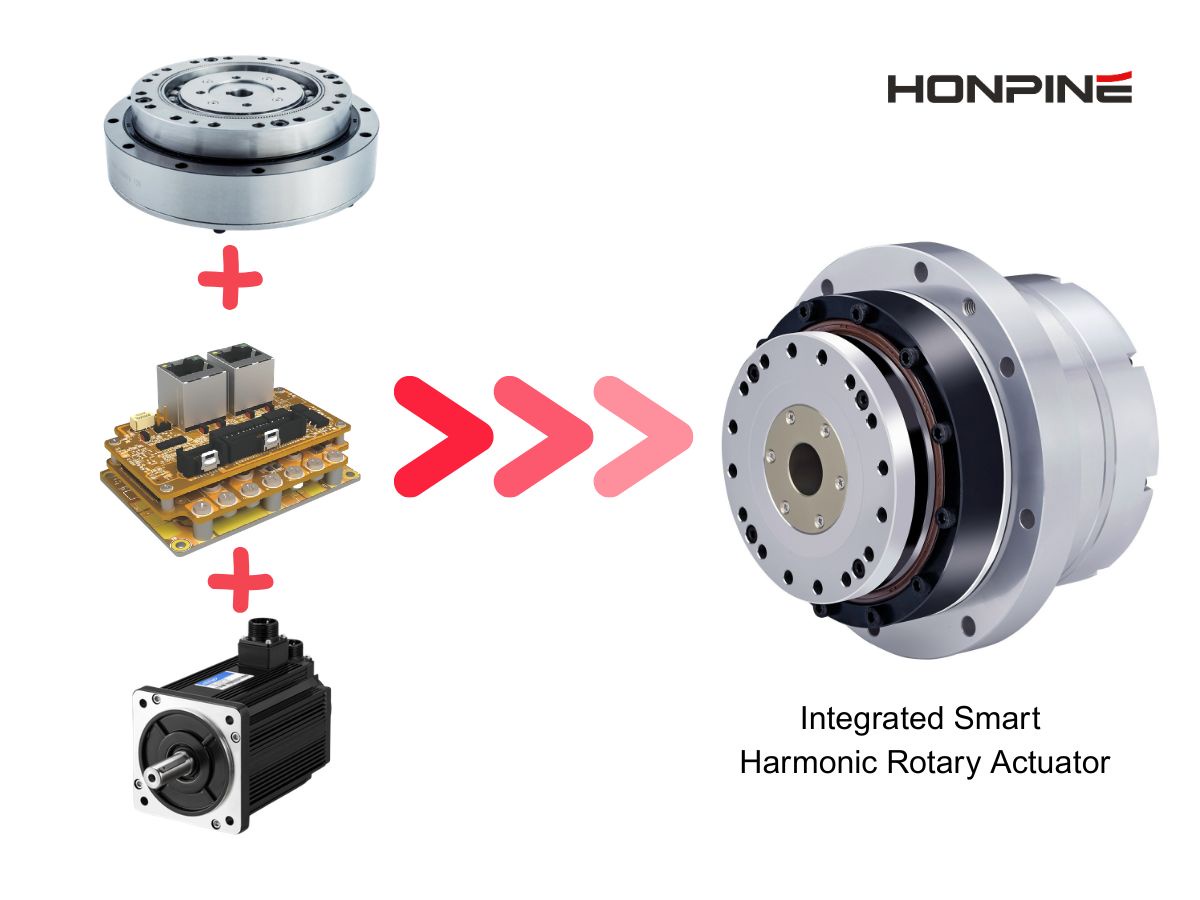

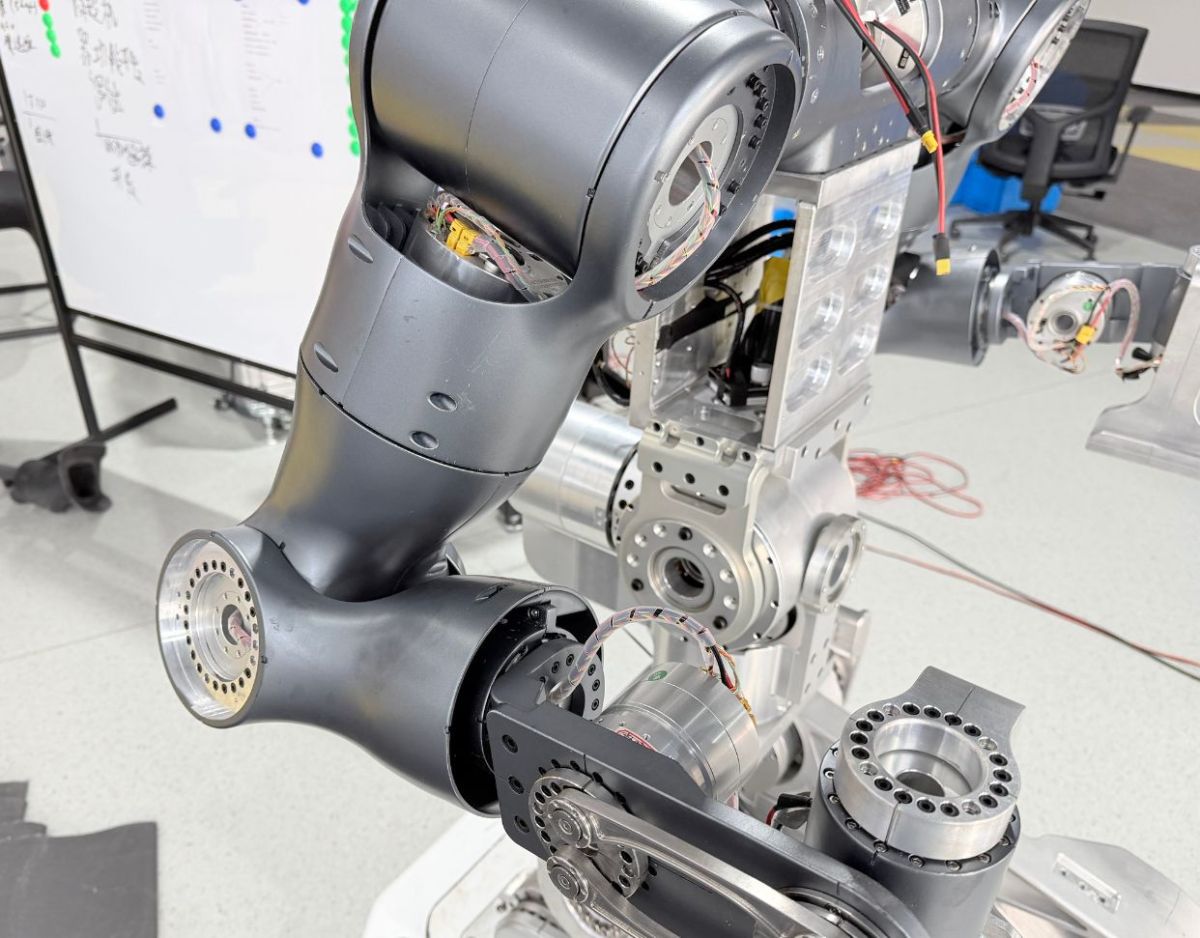

Joint motors (this article mainly discusses rotary types) generally integrate a motor, a driver PCB, a reducer, an encoder, and a brake.

Brake

The function of the brake module is to maintain posture during power loss or faults, preventing falling or collapse that could cause danger or damage (especially for vertical joints). In simple terms, it determines whether the robotic arm will drop under gravity once power is cut. For industrial robotic arms, brakes are indispensable—no one wants a massive arm in a factory to crash downward during a power outage. However, in the era of embodied intelligence, lightweight robotic arms have relatively low mass and therefore often do not include brakes in their joint motors.

Reducer

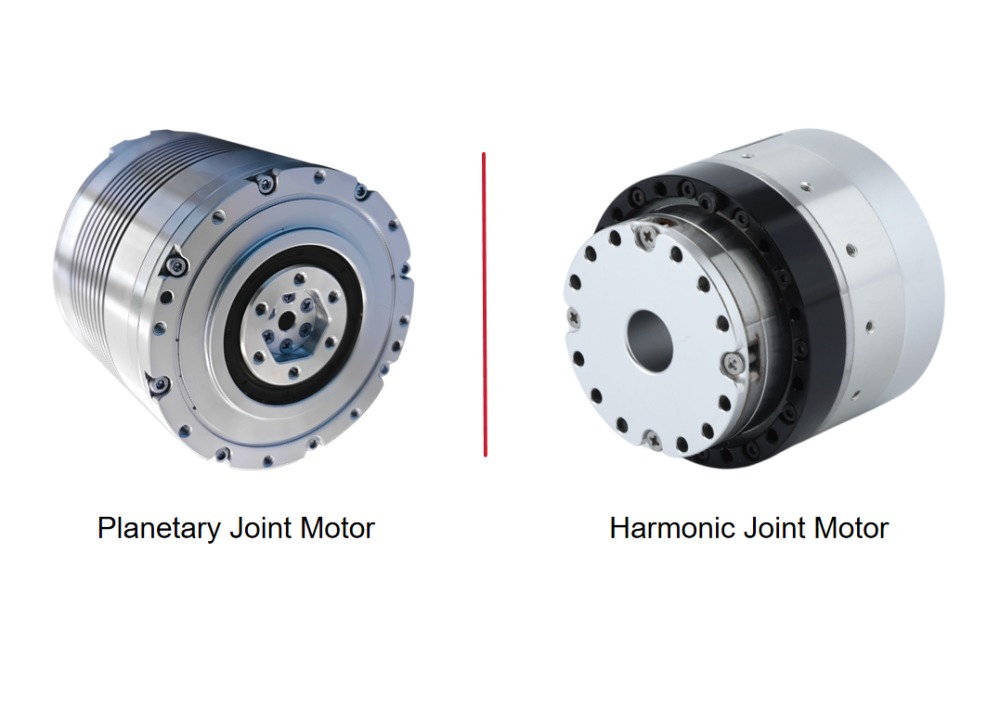

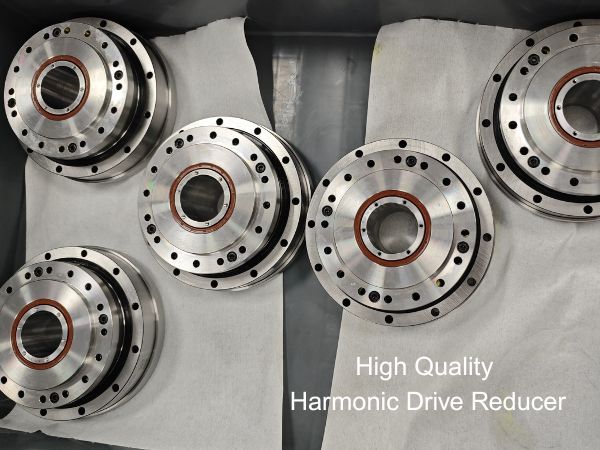

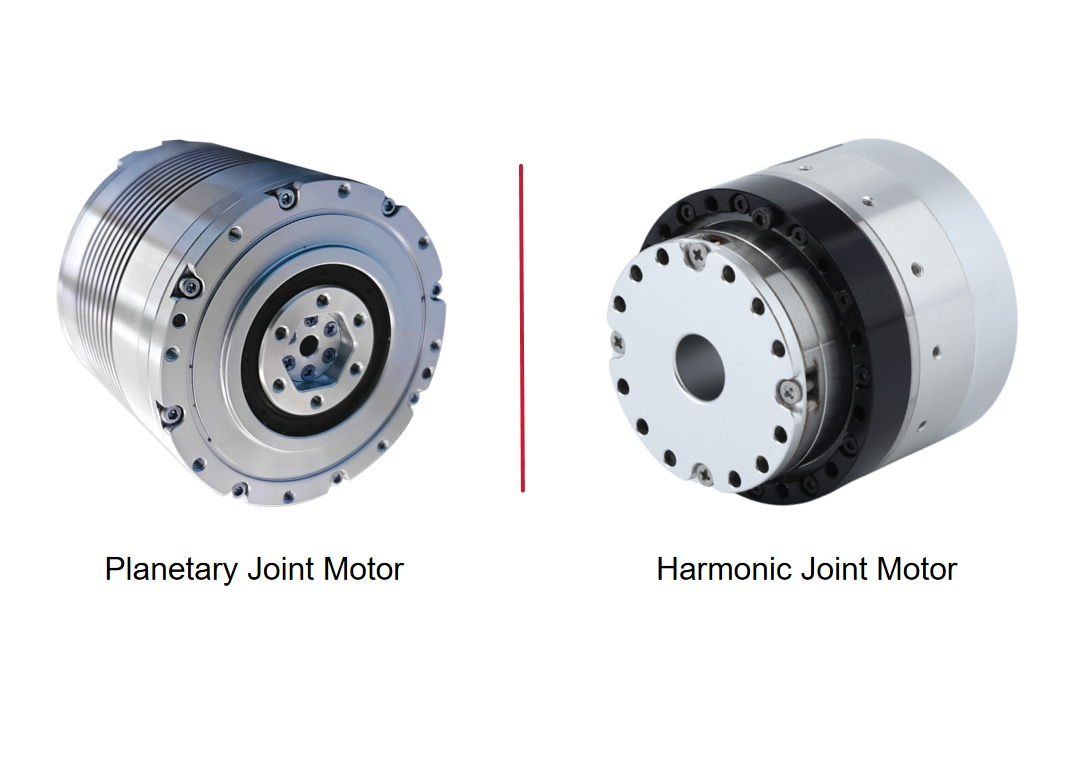

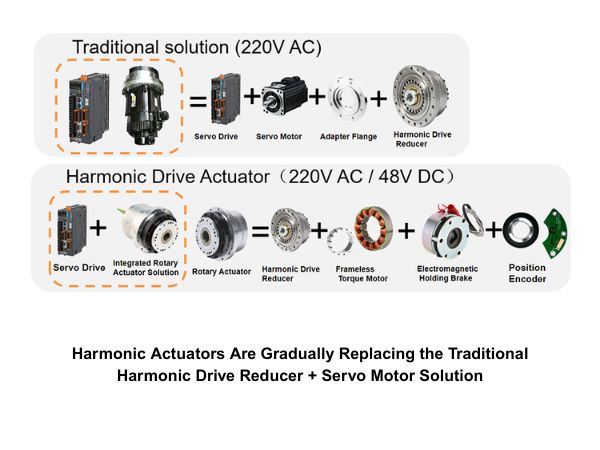

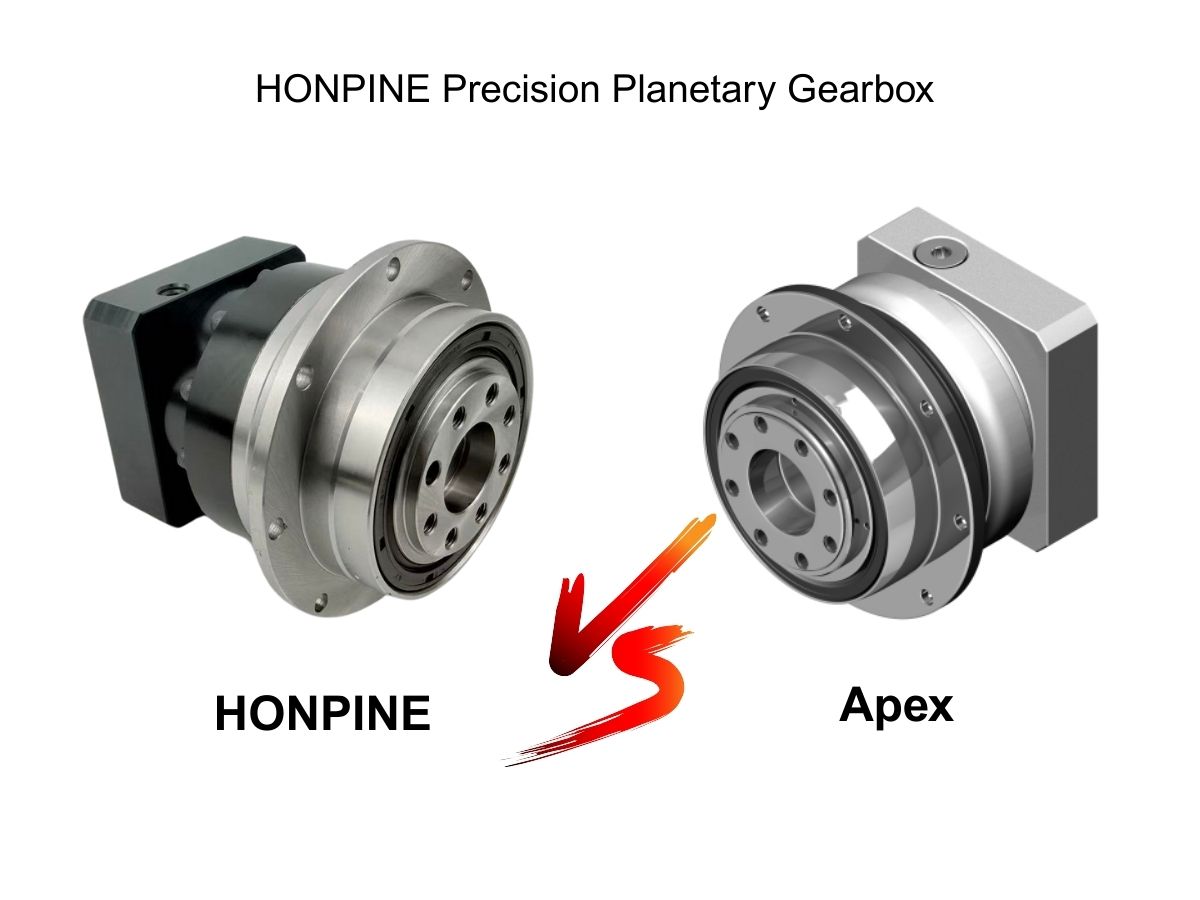

There are generally three commonly used types of reducers: harmonic, RV, and planetary gear reducers. For lightweight robotic arms, harmonic reducers or planetary reducers are most commonly used. Harmonic reducers can achieve high reduction ratios in a single stage but are more expensive. Planetary reducers (especially standard types) typically have much larger backlash than harmonic reducers.

Backlash can be likened to the wobble of a loose door hinge, or the slack in a bicycle chain where pressing the pedal does not immediately move the wheel. In precision machinery, even such small looseness directly affects positioning accuracy.

Encoder

Encoders are mainly used for precise sensing of joint rotation angles. A key parameter is encoder resolution, such as 14-bit resolution. This means that one full revolution is represented by 2¹⁴ = 16,384 pulses, corresponding to a positioning resolution of 360 / 16,384 = 0.02197 degrees.

For robotic arms, absolute encoders are essential: even after power loss, the system still knows the current joint angle. Otherwise, the arm would need to return to a zero position every time it powers up.

Most joint motors use a single encoder on the motor side, which allows precise control of the motor rotor’s position and speed. However, this configuration cannot sense errors introduced by the transmission chain between the motor and the load (such as backlash, elastic deformation, torsional vibration, thermal expansion, or wear in reducers, couplings, belts, or lead screws).

To improve sensing accuracy, some joint motors adopt a dual-encoder scheme: one encoder on the motor rotor side and another on the output shaft after the reducer. By fusing data from both encoders, the system can improve absolute positioning accuracy and repeatability, even in the presence of backlash, compliance, or wear in the transmission chain.

Hollow-shaft motors

A hollow-shaft motor has a central through-hole along its axis, primarily to facilitate cable routing. Wires can pass directly through the center of the motor, avoiding external cable exposure. However, hollow-shaft motors are generally more expensive.

How Do Joint Motors Control a Robotic Arm?

As the most direct actuators in a robotic arm, all control ultimately boils down to joint control.

The most common approach is the three-loop motor control structure:

Position loop: Input = target position; feedback = actual position; output = desired speed (based on position error).

Velocity loop: Input = desired speed; feedback = actual speed; output = desired current (based on speed error).

Current loop: Input = desired current; feedback = actual current; output = adjusted driver voltage (based on current error), directly controlling torque (current is approximately linearly related to torque).

MIT control mode

MIT mode enables mixed control of torque, position, and velocity. Its control block diagram is shown in.

Communication Protocols

Because robots typically have multiple joints and require high-frequency control, communication protocols usually employ CAN bus or EtherCAT. The maximum baud rate of CAN is 1 Mbps. To achieve closed-loop control above 1 kHz, EtherCAT—with maximum rates up to 100 Mbps—is required.

Generally, for a 6-axis joint motor system using CAN bus at 1 Mbps, the maximum achievable control frequency is around 300–500 Hz, which is sufficient for collaborative robots. However, to fully exploit force control at 1 kHz, multiple CAN channels are needed, with each CAN channel driving three motors (as commonly seen in quadruped robot designs).

Selecting robot joint motors is a comprehensive process that balances torque, speed, precision, size, cost, and reliability. From brushed to brushless motors, from stepper motors to servo motors, and from discrete designs to highly integrated joint modules, ongoing technological evolution continues to drive improvements in robotic performance.

Read More

Learn more about the story of HONPINE and industry trends related to precision transmission.

Double Click

We provide harmonic drive reducer,planetary reducer,robot joint motor,robot rotary actuators,RV gear reducer,robot end effector,dexterous robot hand